History

Kyivan Rus

Kyivan Rus is considered to have been founded in 882, when Novgorod’s Prince Oleg stopped in Kyiv on his trip along the Dnieper River. Drawn to the city’s strategic location between Scandinavia and Constantinople, Oleg took over the town. Soon after, he managed to unite the scattered and separated Slavic tribes into a single feudal state - Kyivan Rus. Kyiv became the capital of the newly formed state, and an important political and cultural center of eastern Slavs.

Kyivan Rus was developing most in the 10th century, during Prince Vladimir the Great's reign. In those times, the country spread from the Baltic to Volga, with trade maintaining its economic prosperity – the state lay on the famous trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks. This location allowed Kyivan Rus to maintain its strong political and economical connections with western European countries. In order to strengthen the unity of the state and to increase its influence on the international arena, Vladimir the Great adopted Christianity and made it the state’s official religion in 988.

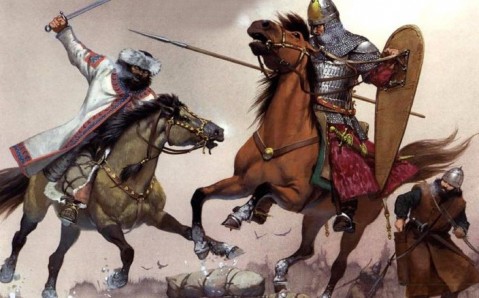

The peak of its feudal power came for Kyivan Rus under Prince Yaroslav the Wise. After his death, however, feudal principalities began to gradually split up, and by the middle of the 12th century, Rus practically fell apart into several independent states. Rus’ enemies did not hesitate to take advantage of the situation. In 1240, after a long and bloody battle, Mongolian Tatars led by Genghis Khan's grandson Batu managed to take over Kyiv. This put an end to Kyivan Rus.

Mongolian Tatars ruled over the Ukrainian territories for almost a hundred years, and their influence spread, in particular, to the southern lands. Later, the Crimean Khanate split from the weakening Golden Horde and occupied the territory of modern Crimea up to the late 18th century.

The Galicia–Volhynia Principality

After collapse of Kyivan Rus, the most powerful principality was the Galicia–Volhynia, created in 1199 after Prince Roman Mstislavich united Galicia and Volhynia. This was one of the biggest principalities of the period: it consisted of modern Ukraine’s western, parts of central, and northern lands.

Due to its geographic position, the Galicia–Volhynia Principality - unlike other Old Russian principalities - managed to escape the catastrophic consequences of the Mongolian Tatar invasion. For a century it prospered, enjoyed independence, and had a great influence in eastern and central Europe.

In the middle of the 14th century, however, Galicia–Volhynia was conquered and split between Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. According to the agreement between Polish King Kasimir and the Lithuanian Prince, Galicia lands passed to Poland and Volhynia became Lithuanian. After this, the Galicia–Volhynia Principality ceased to exist.

The Cossacks

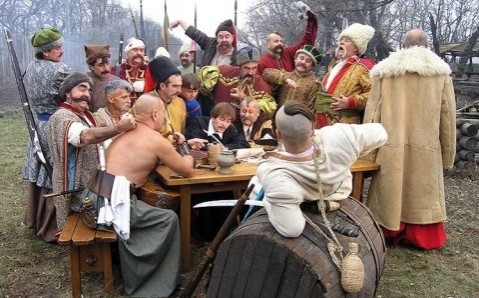

In the second half of the 15th century, the southern territories of lower Dnieper River - lying exactly between the Polish-Lithuanian lands and Tatar Crimea - were scarcely populated. Over time, however, this fertile steppe began to attract refugees who could not stand the poverty and oppression under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as those hiding from religious persecution. Subsequently, these people formed a new estate and named themselves Cossacks (from Turkic "Cossack,” meaning free and independent person, or adventurer). Beside Ukrainians, who made up the overwhelming majority, the Cossack groups also included Tatars, Russians, Poles, Hungarians, and Germans.

The Cossacks’ first settlement, the Zaporizhian Sich, was founded amid the Dnieper rapids, on the Khortytsia Island. It was here that they chose their military commanders - hetmans. Initially, Cossack troops protected the southern borders and repelled Tatar attacks. Over time, however, the Cossacks became skilled in the art of war, fighting not only against the Muslim menace to the east, but also against the Polish magnates’ intensified national oppression.

In 1648, Cossacks led by hetman Bohdan Khmelnitsky rebelled against Poland. The campaign was successful at first - Cossacks defeated the Polish army in several battles and liberated Ukrainian territories. Three years later, however, the Cossacks suffered a crushing defeat, and Bohdan Khmelnitsky had to ask the Russian tsar for help. In 1654, Khmelnitsky signed a treaty with Russia; according to its terms, Russia was to support the Cossacks in their fight against Poland. But instead, the Russian armies fought Poland to gain control of Ukrainian lands. The war ended in an armistice, with Russia gaining control of Kyiv and the land east of Dnieper River, and Poland - the western lands.

Fifty years later, hetman Ivan Mazepa, who did not give up in trying to unify and free Ukrainian lands, decided to join Swedish King Karl XII in the fight against Russia in the Great Northern War. Mazepa's plans, however, would not come to fruition: the Swedish and Cossack armies lost the war.

As part of Russia

Ukrainian lands were particularly important to Russia because they allowed access to the Black Sea. The Azov Sea region and Crimea, however, were still under control of the Crimean Khanate - an ally of the Ottoman Empire. After a number of Russian and Turkish wars, Russia managed to conquer the southern territories and started to populate them with eastern Slavs. Empress Catherine the Great wanted most to liquidate the Zaporizhian Sich, giving her favorite general Grigory Potemkin the order to explore the southern lands and establish new towns here. It was at his behest that the cities now known as Dnipropetrovsk, Mykolaiv, Odesa, and Sevastopol were created.

In the late 18th century, Russia consolidated its control over Ukraine. As a result of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth’s demise, Russia got the territories on Dnieper River’s right bank. The Galicia lands, centered in Lviv, passed to the Austrian Empire.

Civil War, UPR and WUPR

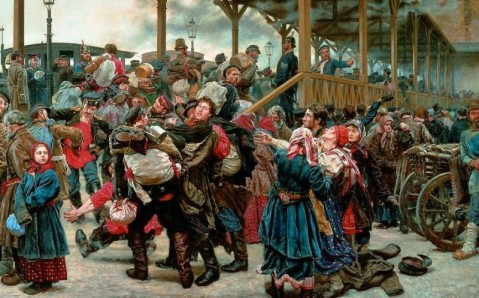

World War I and the Russian Revolution, which resulted in the overthrow of the monarchy, became an opportunity for Ukraine to achieve its freedom. In early 1918, the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), previously an autonomous part of Russia, declared its independence. The Russian Bolsheviks, however, were not going to back down; this started an armed struggle over the issue of Soviet authority in Ukraine.

Over the next several years, Ukraine was the battlefield for grisly confrontations between Bolshevik, Ukrainian, White Guard, Polish, and other forces. The UPR government was not able to uphold Ukrainian statehood, and by the end of 1920, Soviet power was established in the greater part of the country's territory. Ukraine became a Soviet Republic.

At the same time, West Ukrainian territories fought for their independence. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, of which the West Ukrainian lands were a part, collapsed after World War I, and in November 1918, the West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) was created in Lviv. But the young state existed for just eight months. After that, West Ukrainian lands were divided between Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia.

As part of the USSR

In 1922, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) entered the USSR, becoming its second most important republic. A quarter of USSR’s produce was grown on Ukraine’s fertile lands. At first, the USSR was fair to Ukraine, taking into account its interests. The number of Ukrainian schools and universities, for example, grew rapidly. But as nationalism gained steam in Ukraine, Soviet authorities began to fear Ukrainian separatism and abruptly changed their course.

The resulting policies led to a catastrophe in the 1930s. Using so-called collectivization – bringing in private peasant households into collective ones – Soviet authorities (led by Stalin) created an artificial agricultural crisis in the republic that once was the USSR’s and Europe’s breadbasket. In 1932-1933, seven to ten million rural Ukrainians died from hunger.

At the same time, to weed out nationalism, mass political repression was carried out. It reached its peak in 1937-1938, when over 1.5 million people were arrested, one third of whom were sentenced to be shot. Members of the national intelligentsia were beaten.

Ukraine during World War II

But the next period in Ukrainian history was even more tragic, as World War II began. In 1939, the Red Army marched onto the territory of Western Ukraine, which had recently been annexed by the USSR; in 1941, Nazis and their allies started the occupation from here. Over a period of two years, the fascists occupied all Ukrainian cities, completely destroying the majority of them.

While millions of Ukrainians fought in the Soviet army against the occupation, nationalists who never gave up hope to gain independence collaborated with the Germans. The Nazis, however, made it clear soon enough that they did not truly support Ukrainian independence.

During World War II, the partisan movement also became widespread. The guerrilla bands were organized not only by the Soviets, but also by the nationalist forces. The most famous (and the most controversial today) was the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which fought against USSR. But with the war ending in a Soviet victory, Ukrainian nationalists once more lost hope for independence.

Over five million Ukrainians died during the war, and two million were taken to German labor camps. After the war, Stalin exiled several more million Ukrainians, including 250,000 Crimean Tatars, to Siberia on suspicion of betrayal and collaboration.

Postwar development and independence

In 1944, the Ukrainian SSR, along with some other Soviet republics, got the right to choose its external policy and to build up foreign relationships. A year later, after the creation of the United Nations, it became a member of the General Assembly.

Despite the severe destruction, Ukraine managed to quickly revive its economy. Large metallurgical plants and coalmines were rebuilt, and military industries and new electric power plants were constructed in almost five years. Ukraine became the flagship of Soviet industry.

In the late 80s the national movement became prominent once again in Ukraine due to the instability in the USSR. In August 1991 – when USSR was on the edge of collapse – the Soviet governing body proclaimed Ukraine to be independent. This was confirmed by a nationwide referendum in December (around 90% of Ukrainians voted for independence). The former head of the Ukrainian Soviet, Leonid Kravchuk, was chosen as the president of the newly formed state.

The formation of Ukraine as an independent state was not easy, however. The new authorities’ inconsistent reforms worsened the economic crisis inherited from Soviet times, leading to political collapse. This resulted in a change of power in 1994, with Leonid Kuchma becoming Ukraine’s president for the next ten years. He managed to improve the economy, but his second term ended on a low point, with a series of corruption scandals.

The next presidential elections, in 2004, were unprecedented, accompanied by mass public demonstrations against vote rigging. As a result of the Orange Revolution - as the protests came to be called - Victor Yushchenko, the former Prime Minister who had a reputation for being a reformer and following pro-European developmental policies, became Ukraine’s president. He could not meet Ukrainians’ expectations, however, and in 2010, Yushchenko’s opponent Viktor Yanukovich came to power.

Eastern

Eastern